Hiroshi Sugimoto started taking pictures in the 1970s.

Back then, photographers were considered ‘second class citizens’ in the art world, he says at the opening of Time Machine. He used to dream of that changing.

In the past 50 years photography might have become better respected as an art form, but it’s also more ubiquitous. Every one of us takes pictures, and we increasingly treat them as an extension of our own minds, a substitute for our own famously unreliable memory.

That’s why this exhibition at the Hayward – his largest major survey to date – feels so timely. Sugimoto has been playing with photography as a bridge between the internal and external world for over five decades. But what’s fascinating is that he is travelling from the other direction.

Sugimoto doesn’t set out to document reality, but instead uses photography as a means to visualise the ideas formulated in what he calls the “darkroom of [his] own mind”. The images in Time Machine playfully distort the outside world, breathing life into artifice and manipulating natural forces – while trying to find something fundamentally universal about human perception and consciousness.

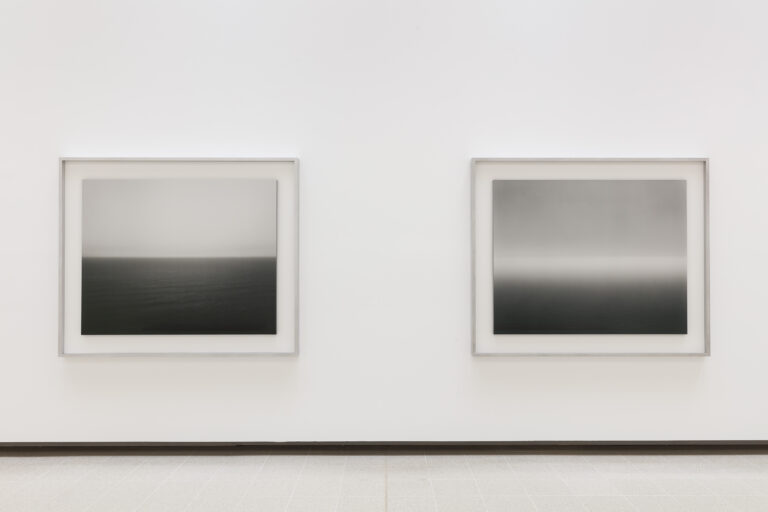

Seascapes. Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery.

For all the serenity of his images on display here, there has been an intensely visceral process behind each one. Sugimoto has developed film by hand, has revisited experiments from the very beginnings of photography in the 19th century, and relentlessly investigates the powers of the camera itself, not just what’s in front of it.

If anything, he deliberately sets out to obscure the real world. His ‘Architecture’ series, begun in 1997, captures iconic buildings around the world using a focal length of ‘twice infinity’ in a bid to see which designs could survive ‘the onslaught of blurred photography’. Here’s the unmistakable arches of the Brooklyn Bridge, the still-distinctive outline of the Eiffel Tower, the peak of the Chrysler Building reduced to shimmering scales. They feel like the recollections of a tourist – not captured on camera, but how they remained in their mind, hazy and intangible. But there’s also something unsettling about them, as though you were drifting in and out of consciousness.

Conceptual Forms. Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery.

The next room brings one of the exhibition’s many effective sudden contrasts. Sugimoto’s Conceptual Forms are close-up shots of mathematical models – spirals, cones and curves – which, scaled-up, possess more architectural force than the real buildings in the previous room. Each figure is a physical manifestation of complex mathematical expressions, and we are introduced to Sugimoto’s mission to make the invisible visible.

In the upper gallery, a series of what appears to be abstract block colour paintings turns out to be shots taken with a prism and Polaroid film, capturing the ‘disregarded intracolours’ in the spectrum of visible light. Reproduced on a large scale, they are strangely enveloping, and new colours seem to emerge from the fog the longer you look at them. Against black, they conjure otherworldly horizons.

Opticks. Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

They’re followed by crisp monochromatic shots resembling forks of lighting or amoeba under a microscope, for which Sugimoto cut out the camera altogether and allowed electricity to flow directly across the film. These feel the closest he gets to ‘instant’ photography in the whole exhibition, and are effectively juxtaposed with his serenely inscrutable seascapes. Sugimoto took these time lapse shots in an attempt to give form to memory – not just of his own earliest memories of the sea, but a kind of collective, primeval memory of a scene that hasn’t changed since the earliest humans became conscious.

The thrust of the exhibition is that, in Sugimoto’s hands, the camera is a time machine – one which can freeze time, stretch or condense it, even physically consume it. This is most powerfully harnessed in Sugimoto’s shots of empty movie theatres, where the camera exposure was set to match the length of a film. Thousands of frames merge into one eerie, luminous rectangle that casts a glow over the rows of seats and, in some shots, the derelict grandeur of the theatre. They feel both spiritual and nihilistic – the film with all its emotional twists and turns has been condensed into a blank, meaningless void.

Theaters. Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

In Diorama, apparently well-timed wildlife shots turn out to be stuffed animals in New York’s natural history museum. Then there are the intimate portraits of high profile figures, which, until you reach Napoleon or Anne Boleyn, you might not notice were actually waxworks from Madame Tussauds. In the original setting you’d immediately realise they were inanimate, but captured on film the subjects are both alive and dead in the same instant.

Sugimoto is a natural artist. The one place where time doesn’t resonate in this exhibition is across the pictures themselves – despite spanning a five decade career, they are timeless, and demonstrate an ingenuity that hasn’t so much progressed as constantly reinvented itself over the years. Now 75, Sugimoto continues to plough his profits back into new ideas and experiments. “Art makes art”, he says.

And only time will tell what art that will be.

NOTE: Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine runs at the Hayward Gallery from 11th October – 7th January 2024. Tickets cost £18, and can be booked HERE.

Hayward Gallery | Southbank Centre, Belvedere Rd, London SE1 8XX

Love art? Check out the best exhibitions on in London now